"Keep 'Em Flying!" Eagle, Idaho's Floating Feather Airport contributed to the war effort, 1941-1945.

Floating Feather Road received its name courtesy of a bush pilot named Willis "Bill" Woods, the survivor of an estimated seventeen to twenty-three crashes over his career, a period in which he logged over 29,000 hours flight time. After purchasing land that would one day become his own private airfield in 1938, Bill began to ponder what to name the airstrip. In recalling some of the crashes he had survived to friends, he recounted how he often brought his aircraft down in rough and windswept territory, floating "down the runway like a feather," swaying from one side to the other. With the issue of naming the airport decided, a runway needed to be established on his 240 acre rectangular parcel of land. The airfield’s main runway paralleled Horseshoe Bend Road to the west, resting between what is the easternmost portion of Floating Feather Road today to the north, and the western end of Dry Creek Cemetery to the south.

After scraping out a gravel runway, Bill and his crew constructed a twelve plane hanger in the southwest section of the airfield. From then on pilots began to earn their wings at Floating Feather, while Bill flew supplies and people into the back country of Central Idaho. Things would soon change at Floating Feather Airfield, as they did for all of America, as World War II worsened and the United States government began to prepare for war. Even before Floating Feather had been established, the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt began forming a reserve of potential combat pilots with the Civilian Pilot Training Program in 1938. By 1939, the Army Air Corp, the United States Army Air Force during and just after World War II and the Air Force becoming its own military branch in 1947, could count a little over 4,500 pilots ready for combat should the need arise. By 1941, 27,000 pilots waited in reserve to fly and fight for the United States. The airfields of the Boise and Treasure Valleys would play their part in this impressive feat of military mobilization and training, Floating Feather included.

Many more pilots would be needed in order for the United States to challenge the Empire of Japan and the Third Reich. The Army Air Corp did not possess enough flight instructors to train all the pilots the nation would need, so the military sought the help of civilian flight instructors and would be combat pilots. From 1939 to 1944, the National Museum of the United States Air Force estimates, 435,165 pilots were trained by the CPTP. Floating Feather Airport, Bill Woods, and a few of his instructors, including Helen Richards - one of only a few female flight instructors to instruct men - played a part in this story by flying with pilots during their “elementary” level flying courses. Instructor Richards would go on to fly for the Women's Auxiliary Ferrying Squadron (WAFS), a small group of women pilots with the directive to “ferry USAAF (United States Army Air Forces) trainers and light aircraft from the factories,” to airbases, but also began to deliver “fighters, bombers and transports as well.” Helen and her fellow flight instructors in the valley did a remarkable job, with 211 college age students from Southern Idaho and Eastern Oregon, a handful of women included, graduating CPTP training programs in the valley with Floating Feather contributing a class of ten to the overall cohort of new fliers in 1941.

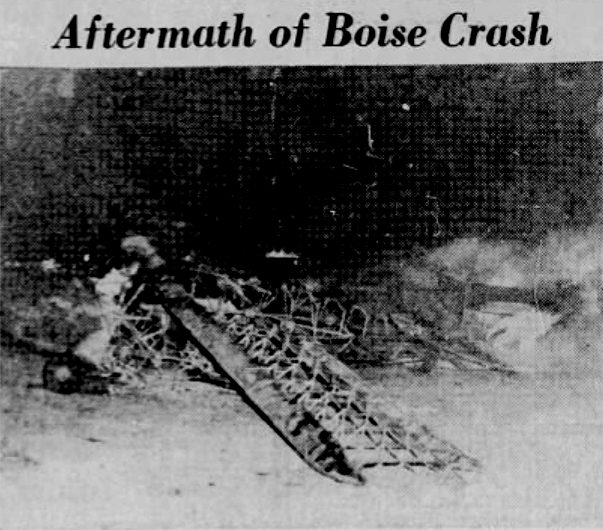

With so many new pilots filling up the airspace of the Boise and Treasure Valleys, tragedy was bound to occur and, unfortunately, Floating Feather and its staff would experience such an event on the evening of June 29, 1944 at approximately 9:30 pm when a B-24 Bomber, or Liberator, crashed into the runway near Eagle, Killing eight members of an eleven man crew. They had taken off from Gowen Field, named after Pilot Paul Gowen of Caldwell who had himself perished in a plane crash, at approximately 9:10 pm. Witnesses said the plane started to burn and break apart somewhere over the location where 22nd Street in Boise intersects with Hill Road. Reportedly, pieces of engine and fuselage began to fall from the plane at an elevation of approximately 500 feet. A member of the crew jumped from the plane, witnesses stated they saw no parachute open. Two others also jumped with their parachutes working effectively. The pilot tried to bring the plane down on the runway at Floating Feather, but the condition of the aircraft made this impossible, and the B-24 Liberator hit face first, exploding in a fireball before careening into Bill Wood’s newly built hangar. Incredibly, a member of the flight crew crawled from the tail of the bomber and article in the Idaho Statesman from June 30, 1944 states.

The names of the deceased pilots are:

Second Lt. James Southard of Gloucester, NY.

Second Lt. Edgar B. Martin Jr. of Syracuse, NY.

Second Lt. Neil C. Von Arb of Kansas City, Mo.

Corp. Forest E. Freeman of Simpson, Kas.

Corp. James H. Lamm of Ellenboro, W Va.

Corp. Welton E. Pagenkopp of Santa Ana, Calif.

Pfc. Vernon R. Dennis of Kansas City, Mo.

Pfc. Paul H. Frahley of Alexandria, Va.

The trail of fuel and wreckage from the plane set wildfires all along the expanse of the foothills running from West Boise to Floating Feather Airfield. The plane left Gowen Field because it had become a training center for B-24 Liberators in 1942, as well as B-17 Flying Fortresses in 1941. Other crashes had occurred prior to 1944 as well. A B-17 had gone down on April 25, 1943, crashing into one of East Boise’s foothills. Three men died in the wreck and six survived. After crashing, Lt. Raphael R. Strauss climbed through the foothills looking for help when he ran into a rescue team of three men sent to find the wrecked crew, one of the three was famous star of stage and screen “Jimmy” Stewart, or Lt. James Stewart if you prefer. This must have been a surreal experience for Lt. Strauss.

Other crashes occurred in Idaho and the rest of the country; bombers were large, heavy duty, weapons of warfare that took a lot of knowledge and precision to operate. Many pilots and crews knew the risk of flying combat missions, but most did not believe they’d perish while being trained to fight. Yet, the many servicemen and women who died while in training deserve just as much respect as those that fell in combat, for they also chose to offer what Abraham Lincoln called their “last full measure of devotion,” to their country and fellow countrymen.

Floating Feather continued on as an Airport until 1972, when Bill Woods sold off most of the airport. He died in 1974. On February 8, 1994, the City of Eagle annexed 95 acres of the original 240 acre lot. Homes now fill the space where pilots were trained for the possibility of fighting in the skies over the Pacific or Europe as cadets of the Civilian Pilots Training Program. Likewise, suburbia now sits where eight men lost their lives while serving their country and where, just across the fence line separating the “burbs” from Dry Creek Cemetery, a line of bronze gravestones form several lines commemorating the veteran’s buried below, yet there is no monument to the pilots and crew who died perhaps fifty yards away.

Image 1: Floating Feather Airfield new hangar and buildings in 1958. The patch of ground south of the airfield is now Dry Creek Cemetery's western portion. Photo is courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department and the Idaho State Archives.

Image 2: Bill Woods and his dog Rags on top of an airplane. Idaho Statesman

Image 3: Floating Feather Airfield in 1958 sitting alongside Horseshoe Bend Road. Courtesy of the Idaho Transportation Department and the Idaho State Archives.

Image 4: Aerial of the Floating Feather Runway and Horseshoe Ben Road in the 1940s. Courtesy the Idaho State Archives.

Image 5: The 1941 CPTP graduates from Floating Feather Airfield. Idaho Statesman.

Image 6: CTPT Instructor Helen Richards in 1942. Idaho Statesman

Image 7: B-24 Liberator (Bomber) taking off from Gowen Field in 1944. Courtesy the 458th Bombardment Group.

Image 8: Crash aftermath on June 30, 1944. Idaho Statesman.

Image 9: Bill Woods Examines the burned hangar. Idaho Statesman.

Image 10: Ad for the CPTP - Circa 1941/42. Idaho Statesman.